Treating dissociation at times can feel like groping around in the dark. We know we are in the right ballpark, but every session can be an act of straining to interpret and understand what is being presented. Ever since I started doing treatment and parenting as a therapeutic foster parent, I wanted desperately to have a decoder ring to understand what was going on, and how to engage and respond. In my pursuit, I have connected with Fran Waters, LMSW, DCSW, LMFT to understand her STAR Theoretical Model (Waters, 2016) as a framework or a lens to make sense of what was being presented by my clients and foster children. Waters’s (2016) work was built off a model that she developed as she worked with dissociative youth.

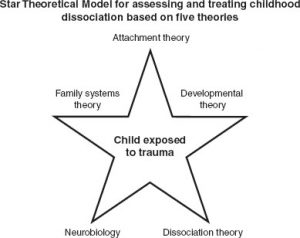

The model that was created in order to develop a framework for understanding the mental health presentations that she was seeing in these youth. Initially, she created what she coined the Quadri-Theoretical Model which incorporated the work of attachment theory (informed by Bowlby) , developmental theory (informed by Erikson), family systems theory (informed by Satir), and dissociation theory (informed by Janet, Putnam, Van der Hart, Watkins, Silberg, and Freyd). As she was influenced by neurobiology, she adapted this model into the Star Theoretical Model (STM) because the findings were helpful in understanding the diagnostic makeup of dissociation.

The purpose of the model can be summed up as a tool that “describes pathways that either lead to, or influence the use of dissociation in children and adolescents, and it guides the assessment and treatment of children with dissociation” (Waters, 2016, p. 4). The impact this has had on my treatment of my clients is significant because the behaviors presented now made sense and were supported by the vast resources within the fields of study in dissociation, attachment, neurobiology, family systems, and developmental psychology. In order to show how the STAR model can be used for case conceptualization and treatment, I will share a vignette from one of the clients I treated. (All names and details have been changed for confidentiality purposes. Vignette inclusion was approved by the client and her family.)

A 13-year-old girl, Charlotte, came to my office with her family in order to receive treatment for what they suspected to be Dissociative Identity Disorder. The family had been through several different treatment protocols and medication regimens. In addition, their daughter experienced several hospitalizations that were ineffective in helping her stabilize and heal. Charlotte came into therapy identifying several parts of self, each with their own names, purposes, and backstories concerning their “lives” before they came to be a part of Charlotte. These parts of self came to be as a result of significant childhood sexual abuse by a peer over the course of several years. The initial assessment of this youth began with assessing the dissociative symptomatology by going through an A-DES assessment which indicated that a dissociative disorder was possible. Further assessment and clinical interviewing solidified this diagnosis. I then began to assess through Waters (2016) Sixteen Warning Signs of Dissociation, recognizing indicators of dissociation related to Charlotte’s traumatic history, moments of switching and the presence of different parts.

The next stage of utilizing the STAR model was the intervention of psychoeduction for the child and family about dissociation and communicating the treatment goal of integration. I put a special emphasis on communicating to the child’s system how “brave and strong they are”, and how “my goal was not to get rid of the parts but to help them work together”. I also spent significant time focusing on safety building so that the child and her parts knew that I was not going to harm them and would pace our work according to what she and her states could tolerate. The psychoeducation of dissociation is a crucial step because it allows the therapist to conceptualize the behaviors and symptoms for the family to make it understandable with clear guidelines for stabilization of behaviors. Assessing attachment is something done over time by tuning into the relational dynamics with the parents by including them in sessions. This can help build safety in the sessions as well because the parents are more attached to the child than the therapist, and because attachment is central to treatment. Attachment wounds and betrayal trauma must be worked on and resolved to move towards integration.

Charlotte’s relationship with her mother, while being secure at times, suffered because the abuse of a peer happened in her own home, where the child felt the parent should have protected her. This was learned in the assessment phase of treatment and during the treatment phase, I circled back to this dynamic when a part of self that primarily held the rage towards its abuser took unilateral control for a couple months. As part of therapy, Charlotte’s mother, father, and her sister (with whom there is relational disconnect as well) wrote letters to Charlotte about how they were sorry she experienced the abuse and that they wished they could have protected her and stopped those events from happening. That was a stepping-stone to ‘grease the wheels of treatment’ because that dissociative part largely wanted to disengage and stop going to therapy, due to not wanting to address the homicidal behaviors it presented with.

These homicidal behaviors were a means for this perpetrator introject to protect the child by redirecting the rage on her attachment figures. That part would often state “if my parents or sister were dead then I would not have to feel like this anymore, and even if I went to jail or was sad that they were gone that feeling would go away also”. This all indicated attachment needed to be addressed to continue to work through the trauma. The influence of neurobiology is also a helpful psychoeducational piece for the parents to understand the impact of trauma with the polyvagal theory, and how stress is a mitigating factor in whether the child can stay within their window of tolerance or feel the need to rely on switching between parts. That allowed the parents to understand what was happening inside their child’s mind. Within the assessment and the treatment stages, there is always an awareness of tuning into the child’s window of tolerance and being aware of stress and how to elicit safety in therapy sessions.

If a child is resistant and non-participatory, then stress is elevated, safety is questioned and parts are presenting with a myriad of behaviors to distract and disrupt momentum in treatment. I encouraged the parents to use their new understanding of the neurobiology of trauma to adjust their parenting approach. The golden rule when treating dissociative youth in this model is ‘connecting before correcting’ (Hughes & Baylin, 2012; Siegel & Payne Bryson, 2014) because it causes the parent to become curious about the child’s behavior to understand how the trauma is playing out specific behavioral coping scripts. It also allows for attachment repair to happen in the moment of triggering. Charlotte’s different parts presented differently but they all tended to move into scripts that distanced and withdrew from family members, which led Charlotte to hide up in her room for significant lengths of time. The parents were bothered by this and wanted to correct it, but the tuning in of ‘connecting before correcting’ allowed Charlotte’s parents to move towards her and drew her out of seclusion into connection with them through cuddling, and one-on-one time.

Developmental psychology is a lens that allows for understanding where and what is going on within a dissociative child’s system. In the assessment phase, we were able to explore each of the different parts and identify developmental stages for each part. The little parts were younger developmentally and did not have the fine motor and academic skills needed for Charlotte to function in school. Therefore in several sessions, I worked on helping the younger parts identify why and when they are triggered to come out and also helped them feel comfortable staying inside when the child was in school so that they could avoid times when Charlotte switched and became lost, frightened and disoriented in school. This goal is a short-term focus to allow for stability as the goal will eventually to developmentally grow the different parts up. The younger parts need to orient to the present where the child is safe and older so that different developmental stages do not conflict with current functioning.

I worked together with Charlotte’s parental part (who took on the role of raising up one of the little’s) by helping the young part have internal space and tools to feel comfortable staying inside and also allowing for this part to have internal glasses (installed through EMDR) to help with the learning and growth process. Through this intervention, this younger part has grown to become an integral part of treatment because this part has been found to have influence or control over the perpetrator introject part of Charlotte’s system, allowing for therapeutic resistance to treatment to be mitigated. Family systems work is key to understanding the child’s internal system because their internal systems mimic the systems in their birth and adoptive homes.

Having a strong understanding of the family’s dynamics and roles helped me to understand what roles the internal parts had taken. Charlotte’s mother presented with her own trauma history and presented with a diagnosis of OCD. Charlotte’s system created a part of self that was oriented around parenting and is meticulous and controlled about the internal family and its dynamics, which seemed to mimic some traits similar to her mother’s OCD. This part had schedules, routines, educational lessons that it would force the internal family to follow through with. There is also a part of self that is predominantly image-conscious and self-focused. This part tended to take after Charlotte’s older sister, which plays in the same family patterns because Charlotte was distant and not connected to this part of self, and often remarked on hating this part. In order to work through the internal family dynamics, we helped her external family dynamics.

Charlotte would not be able to heal and integrate with her self-oriented part that mimicked traits of her sister if she did not work through the dynamics with her actual sister, and the same was true for her relationship with her mother. The reasoning can be quite symbolic and different for every child’s system, but for Charlotte, it was because each of those family members hurt her in different ways, so their behavioral scripts were wrapped up in pain and needed to grieve and unburden from those dynamics. These five pathways can provide the therapist with a concrete assessment and foundation to treat these children. It gives hermeneutics, direction, and creates open windows for stabilization, and integration to take place.

Charlotte’s system improved significantly when stabilization and safety were achieved by utilizing these 5 pathways in the STAR theoretical model. It also allowed for clarity when treatment became a challenge and Charlotte was resistant. The model helped me interpret and identify a perpetrator introject and understand the impact of the family and attachment dynamics in play. The STAR Theoretical Model (Waters, 2016) is a comprehensive and directional primer and approach to treating dissociative clients.

References: Hughes, D. A., & Baylin, J. (2012). Brain-based parenting: The neuroscience of caregiving for healthy attachment. New York, NY: W. W. Norton. Siegel, D., & Payne Bryson, T. (2014). No-drama discipline: The whole-brain way to calm the chaos and nurture your child’s developing mind. New York, NY: Random House. Waters, F. S., (2016). Healing the fractured child: Diagnosis and treatment of youth with dissociation. New York, N.Y., Springer Publishing Company.