Child sexual abuse is an extensive health problem in the United States (U.S.) and leads to a variety of serious mental and physical health issues throughout the lifetime of the individual (Townsend & Rheingold, 2013). Short and long term consequences include exacerbation of autoimmune diseases, labile affect, dissociation, mood dysregulation, poor self-esteem, and problems related to boundary formation (Bass & Davis, 2008; Chew, 1998; Courtois, 2014; Dube et al., 2009; Finkelhor, 1986; Kaufman & Wohl, 1992). The child’s and later the adult’s world view is altered, and his/her attachments and relationships are fragmented. Trust in him/herself and others has been trampled. Judgments are distorted and cognitive functioning can become compromised. Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), mood disorders, substance use, eating and sleeping disorders, and suicide risk are also significantly elevated in both childhood and adulthood (Bahk, Jang, Choi, & Lee, 2017). A variety of therapies have been developed and implemented to help victims cope and heal from the psychological repercussions of childhood sexual abuse. Play, sand tray, and art therapies have been instituted to help these child victims recover, with considerable degrees of success (Bratton, Ray, Rhine, & Jones, 2005; Homeyer & Sweeney, 2016; Pifalo, 2006).

This makes sense, as these therapies simulate the child’s own natural strategy of healing him/herself in a non-threatening context. Bibliotherapy, the use of storytelling as part of the healing process, which is the focus of this writing, offers several advantages in terms of giving children healthy instead of destructive coping skills. As Dr. Pardeck describes, the sexually abused child can learn and begin to heal through stories that demonstrate how the characters resolve their issues and translate these lessons into their own lives (Pardeck, 1990). He believes “conventional talking treatment” is difficult for abused children because they have been silenced through their abuse. This pattern is perpetuated into adulthood; adult patients who attempt to talk about their childhood abuse are often unable to do so. Bibliotherapy encourages curiosity instead of an automatic fear response. The child is engaged and may be thinking, “I wonder what will happen next?”

The picture book fosters a sense of calm instead of activation. As the story progresses the nervous system regulates. The stories, in fact, can be used to help the kids experience a narrative in a more regulated manner. Engendering a sense of calmness, bibliotherapy also incorporates mindful meditation, that is, paying attention on purpose, as both the therapist and child focus together in the moment of the reading. All other sounds and sensory input are quieted and subtly fade into the background. The engaging characters and illustrations assist in creating a “laser focus” in which distractions are minimized. It is well-known that autonomic nervous system dysregulation can occur subsequent to sexual trauma (Keeshin, Strawn, Out, Granger, & Putnam, 2014; Lorenz, Harte, & Meston, 2015). In particular, the polyvagal theory posits that when the brain processes emotionally-salient stimuli (whether externally- or internally-driven), it outputs this information to the cranial nerves, including the vagus nerve, which in turn influences heart rate, breathing, and muscle tone in the pharynx and larynx (Porges, 2009).

Examples of this can be witnessed in the breath of the child. Shallow breathing is an observable defensive state, while mouth breathing is generally associated with hyper-arousal. When a child is dysregulated in this way, his/her cognition is “off-line.” One of the goals of therapy is to assist the child in maintaining him/herself within the window of tolerance of emotions using imagery, five-sense perception and physical sensations. In a similar vein of combining cognitive and physical elements, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a cognitive, affective, and somatic approach to trauma therapy (Shapiro & Forrest, 2016). It is a treatment in which painful material and beliefs about the self, are processed with the use of bilateral stimulation.

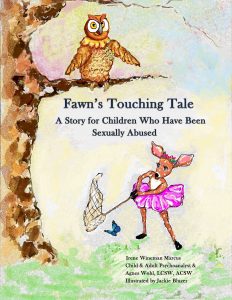

The beginning stage of this treatment is resource building where the child is urged to create more adaptive skills to face the past and function in the present. Reading a children’s picture book aloud with bilateral stimulation (usually the use of tappers), enhances the reading and deepens the messages of the book. Most often, children who have been sexually abused have disturbed attachment formation (Alexander, 1992; Ogden & Fisher, 2015; Riggs, 2010). The idea of a secure connection to the primary care giver is generally absent in these cases. The resource of awareness, that somebody is there for the child, whether he/she is physically present is poorly developed in these children. Bibliotherapy can be utilized to begin to foster learning of secure attachments. Children who have been sexually abused often feel they are the only ones who have suffered this fate. Reading a book with animal protagonists can be a non-threatening way to introduce the concept that this is a trauma that happens to others and they can overcome it. “Fawn’s Touching Tale” is a story about a family of deer in which the daughter is sexually abused by her father, and an owl is metaphorically the therapist (Wohl & Marcus, 2018).

It takes the reader through the process of the grooming, the sexual abuse, and the beginning of resolution. The child can comfortably make the connection that firstly, this is not his/her problem alone; this happens to others, and it creates a sense of hope: that there can be some form of resolution. This story and many others have the capacity to provide a container for difficult emotions, cognitions and experiences. It can start the process of encouraging the child to create his/her own narrative as they re-remember their own story in the presence of an attuned therapist in the present moment. The memory that was unpacked is now repacked in a different, more adaptive way (Ogden & Fisher, 2015) The best approach to treating child sexual abuse is one that is tailored to the individual child. Thus, the clinician should be well-versed in all the different types of therapy available and titrate them to meet the needs of each child, much as a psychopharmacologist might use a combination of titrated medications. Although it is likely that most if not all patients will be equally receptive to bibliotherapy, both children as well as adults who enjoy storytelling and being read to are inclined to benefit from this form of therapy. Acknowledgements: We thank Dr. Howard Kirschen MD for his critical feedback on this manuscript.

References

Alexander, P. C. (1992). Application of attachment theory to the study of sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol, 60(2), 185-195.

Bahk, Y. C., Jang, S. K., Choi, K. H., & Lee, S. H. (2017). The Relationship between Childhood Trauma and Suicidal Ideation: Role of Maltreatment and Potential Mediators. Psychiatry Investig, 14(1), 37-43. doi:10.4306/pi.2017.14.1.37

Bass, E., & Davis, L. (2008). The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse, 20th Anniversary Edition. Collins Living.

Bratton, S., Ray, D., Rhine, T., & Jones, L. (2005). The Efficacy of Play Therapy With Children: A Meta-Analytic Review of Treatment Outcomes. Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 36(4), 376-390.

Chew, J. (1998). Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse: Healing Through Group Work, Beyond Survival. Haworth Press.

Courtois, C. A. (2014). t’s Not You, It’s What Happened to You: Complex Trauma and Treatment. Elements Behavioral Health.

Dube, S. R., Fairweather, D., Pearson, W. S., Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., & Croft, J. B. (2009). Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosom Med, 71(2), 243-250. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907888

Finkelhor, D. (1986). A sourcebook on child sexual abuse. Sage.

Homeyer, L. E., & Sweeney, D. S. (2016). Sandtray Therapy: A Practical Manual Third Edition. Routledge.

Kaufman, B., & Wohl, A. (1992). Casualties of childhood: A developmental perspective on sexual abuse using projective drawings. Brunner/Mazel.

Keeshin, B. R., Strawn, J. R., Out, D., Granger, D. A., & Putnam, F. W. (2014). Cortisol awakening response in adolescents with acute sexual abuse related posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety, 31(2), 107-114. doi:10.1002/da.22154

Lorenz, T. K., Harte, C. B., & Meston, C. M. (2015). Changes in Autonomic Nervous System Activity are Associated with Changes in Sexual Function in Women with a History of Childhood Sexual Abuse. J Sex Med, 12(7), 1545-1554. doi:10.1111/jsm.12908

Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor psychotherapy: Interventions for trauma and attachment. W W Norton & Co. Pardeck, J. T. (1990). Bibliotherapy with Abused Children. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services.

Porges, S.W. (2009). Reciprocal influences between body and brain in the perception and expression of affect: A polyvagal perspective. In D. Fosha, D. Siegel, & M. Solomon (Eds.), The healing power of emotion: Neurobiological Understandings and therapeutic perspectives.

Norton. Resick, P. A., Nishith, P., Weaver, T. L., Astin, M. C., & Feuer, C. A. (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. J Consult Clin Psychol, 70(4), 867-879.

Shapiro, F., & Forrest, M. S. (2016). EMDR: The Breakthrough Therapy for Overcoming Anxiety, Stress, and Trauma. Basic Books.

Townsend, C., & Rheingold, A. A. (2013). Estimating a Child Sexual abuse prevalence rate for practitioners. CALiO Collection of Resources.

van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma 1st Edition. Penguin Books.

Wohl, A., & Marcus, I. W. (2018). Fawn’s Touching Tale: A Story for Children Who Have Been Sexually Abused. Independently Published.