Given October is Domestic Violence Awareness month in the US, we offer this book review by Jackie Burke, long term member of ISSTD, a psychologist in private practice in Sydney Australia, and Adjunct Fellow at Western Sydney University.

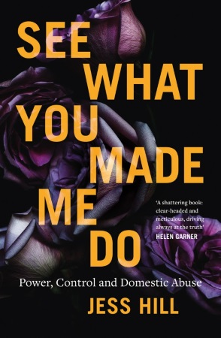

Published last year, Jess Hill’s book, See What You Made Me Do: Power, Control and Domestic Abuse won the 2020 Stella Prize and the Australian Booksellers Choice for Best Non-Fiction Book of the Year in Australia. It was a finalist for a Walkley award and the Australian Human Rights Commission Media Award. Hill is no stranger to such accolades with three awards from Our Watch – Australia’s Centre of excellence on primary prevention of violence against women, and two Walkley awards under belt, and a distinguished career in journalism encompassing a specific focus on domestic violence since 2014. The book is so popular that a version tailored to UK readers was released in August 2020, and an American version is available from 01 September 2020.

So, what is it about Hill’s book that is such a game changer?

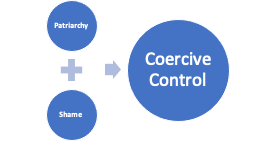

Firstly, it is brave. Hill succeeds by thoroughly researching her topic and presenting a measured account of differing viewpoints rather than towing a particular line on this evocative and polarized topic. In particular, her analysis of the etiology of domestic violence excels by moving beyond standard discourses of patriarchy or psychopathology and marrying the two with an equation that suggests that it is in the interaction between patriarchal constraints around men’s success, and shame based psychological wounding from powerful experiences of being controlled (usually during childhood) that precipitates coercively controlling behaviour. This articulation helps readers to comprehend how coercive controllers often construe themselves as the victim within the relationship rather than the other way around. It also explains how there can be markedly different levels of consciousness about controlling behaviour amongst those who use control.

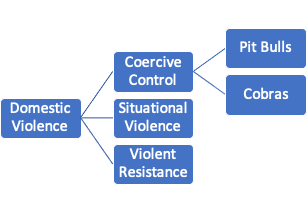

Secondly, Hill’s work situates perpetrators of coercive control in everyday suburbs and regular homes, explaining how many coercive controllers only use controlling behaviours in their primary relationships and so not only look like nice guys to the outside world but also uphold a view of self as decent despite their controlling and/or violent behaviour. This usefully challenges common myths that discount the prevalence and harm associated with domestic violence, and situate domestic violence as occurring only within some communities rather than all. Hill’s analysis of coercive control is clear, and she presents an approachable articulation of Gottman and Jacobson’s (2007) categorization of Pit Bulls and Cobras. Importantly, violent resistance is also well covered.

What isn’t covered so well is the prevalence of coercive control without physical violence. A frequent and psychologically harmful aspect of domestic violence that is often unfortunately overlooked in the understandable haste to gain traction on issues of physical risk. Were this information more widely available, such as in books like Hill’s, it could facilitate early identification of unsafe behaviours, and thereby mitigate both psychological and physical harm from coercive control. The book could also have benefitted from articulating just how effective coercive control tactics are, a concept well outlined in McMillan’s (2007) book, But He Says He Loves Me.

Hill’s empathic chapter on domestic violence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities, and her argument that there is more evidence of a culture of violence from Britain than from Indigenous Australia, contributes to a necessary end to the erroneous notion that domestic violence is an aspect of culture for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. A more thorough analysis of different etiologies of domestic violence such as that outlined more recently by Nancarrow (2019) may have added meaningfully to this section.

Naming the impacts on children of growing up in a violent home as C-PTSD and including dissociation as a key strategy for coping, is commendable.

Hill’s book presents an up to date analysis of domestic abuse in Australia that is thoroughly researched, measured, and well-articulated. It is essential reading for anyone working with people affected by domestic and/or family violence, or relationship distress more generally. In addition, it presents an important call for change especially in relation to legal and judicial responses to domestic violence particularly in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities.

References

Gottman, J. and Jacobson, N. (2007). When Men Batter Women. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Hill, J. (2019) See What You Made Me Do. Carlton, Vic: Black Books.

McMillan, D. (2007). But He Says He Loves Me. Allen & Unwin.

Nancarrow, H. (2019). Unintended consequences of Domestic Violence Law: Gendered Aspirations and Racialised Realities. New York: Palgrave.